Earlier this month, The Hollywood Reporter published a sharp piece of cultural analysis titled “Are Music and Other Celebrity Films Killing the Documentary?” Nonfiction filmmakers and programmers interviewed for the feature weighed in on the influence of the major streamers, shifting away from formal invention and probing investigation toward authorized, artist-friendly docs that function primarily as marketing, brand management and fan service. Alison Ellwood’s Boy George & Culture Club is a solid example of this anodyne trend. It’s candid but seldom reveals much that’s fresh, as infectious as one of the Brit new wave band’s earworm hits but about as weighty, too.

Still, anyone with fond memories of Culture Club’s heyday will likely be hooked from the moment the harmonica enters in the opening bars of “Church of the Poison Mind,” still one of the catchiest bops of the 1980s, heard here in a concert performance that showcases the powerhouse backup vocals of Helen Terry.

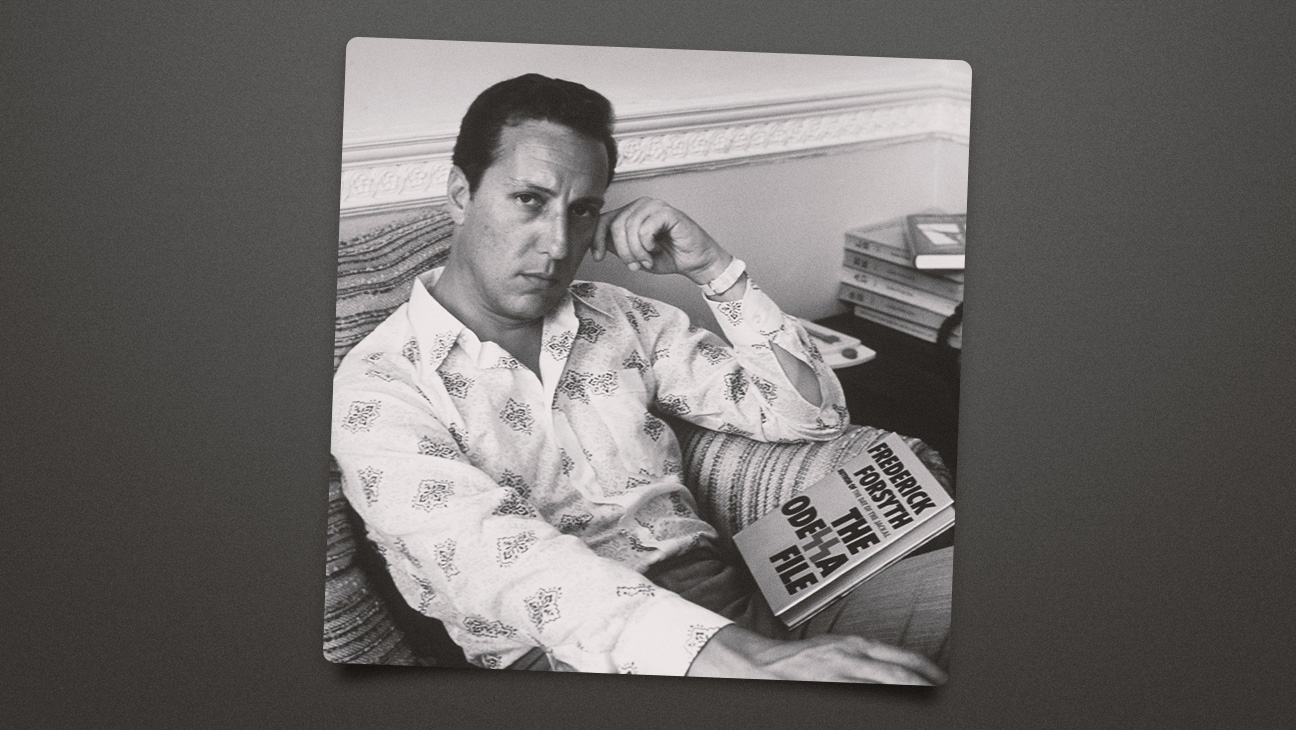

Boy George & Culture Club

The Bottom Line

Gets the job done but lacks perspective.

Venue: Tribeca Film Festival (Spotlight Documentary)

With: George O’Dowd, Jon Moss, Mikey Craig, Roy Hay

Director: Alison Ellwood

1 hour 35 minutes

That song is a welcome reminder that while the band fronted with iconoclastic style by Boy George might have emerged out of the New Romantic scene, their musical influences ran from blue-eyed soul to reggae, Motown, calypso and even a dash of country on “Karma Chameleon.”

But although all four bandmates weigh in extensively in separate present-day interviews, the doc is disappointingly short on insight into how the music came together. As the film would have it, George wrote the lyrics — often displayed in candy-colored ‘80s-style graphics that mimic Culture Club album covers — while the tunes just sort of materialized once the musicians got together in the studio.

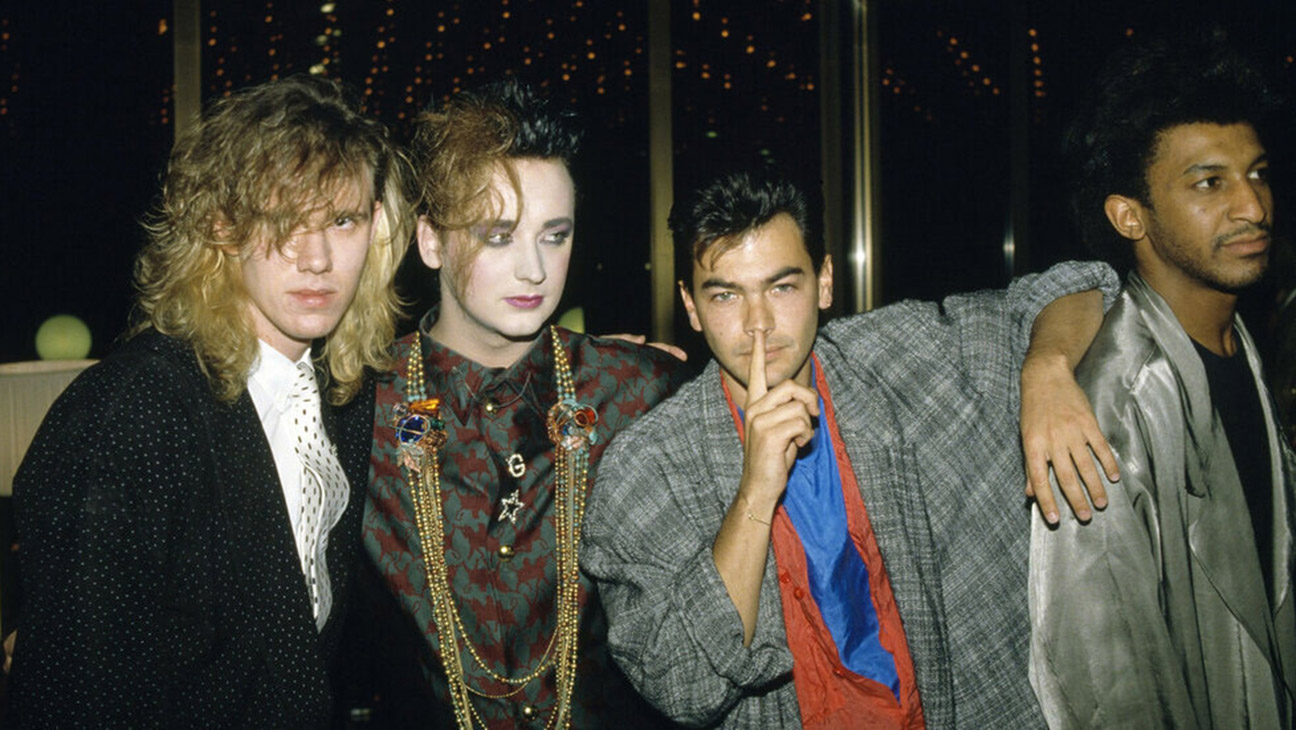

There is of course something to be said for that kind of magical alchemy in a pop band. The name Culture Club itself is a reference to their unusually diverse makeup — a gay Irish lead vocalist; a Black Jamaican Brit bassist (Mikey Craig); a blond Englishman guitarist (Roy Hay); and a Jewish drummer from a punk background (Jon Moss).

Perhaps one reason the four members are interviewed separately is that although they “took some time” rather than officially breaking up in 1986 (and continued to tour on and off for three decades while also pursuing their own projects), the extent to which George’s big personality and transgressive look overshadowed both his bandmates and the music itself — even his own vocal talent — seems to remain a mostly unaddressed sore point.

Footage of the music video shoot for “Karma Chameleon” on a Mississippi riverboat, with Mikey, Roy and Jon standing around looking uncomfortable in 19th century Southern gent finery, speaks volumes about the divide. Later, over a bonkers video for a rare ballad, “Mistake No. 3,” which George describes as “the pinnacle of our excess,” Hay observes: “We were just like George’s little dress-up things.” But it’s hard to consider George insensitive when he looks back at it all through such a humorous lens. “Yeah, I guess the other three felt like they’d been dragged into a gay circus,” he says with a chuckle.

There’s plenty of humor also in individual thoughts on their biggest but frothiest hit. “I think we lost a lot of credibility with ‘Karma Chameleon’,” says Roy. “But it’s the thing we’re remembered for.” Adds George: “They say it was the nail in our cool coffin. But we were never cool! That song went to No. 1 and stayed there for weeks. Tortured everyone.”

George acknowledges his dominant role but pretty much laughs off any frustration the other members might have felt. He comes across as a likeable, frequently very funny narcissist with a diva streak and an unapologetic sharp edge when challenged. That’s not to say his soulful voice and attention-grabbing look were not the crucial ingredients in the band’s 1982 breakthrough with the reggae-inflected single “Do You Really Want To Hurt Me.” And nor do any of George’s bandmates deny that he was their chief fame-driver.

It’s fun to learn how young working-class George O’Dowd transformed into fabulous Boy George, a fixture at clubs like Billy’s and The Blitz, going from a punky blond dye-job at 16 or 17 to full drag within six months. The rise of David Bowie and Marc Bolan was formative, and he talks about the discovery of makeup as a liberation, taking inspiration from Siouxsie Sioux, Poly Styrene of X-Ray Spex and Ari Up from the Slits for the cascading dreadlocks.

With his wide-brimmed hats, dramatic makeup and Technicolor muumuus, George couldn’t help but become the focal point, and while the press mostly danced around the topic of his sexuality at first, he was dismissive of attempts to identify a political viewpoint in his androgynous persona. In one archival interview from the early days, he says they weren’t trying to say anything with their music or fashion.

In some ways, that’s also reflective of Ellwood’s doc, which touches on LGBTQ representation, homophobia and hypocrisy but does so with too little context or overarching perspective to be illuminating. It seems bizarre, for instance, that a film purporting to deal with these subjects in the first half of the ‘80s shows no curiosity about how the AIDS crisis might have fed into negative reactions.

The band had reached its zenith, with Beatlemania-size crowds greeting them in Australia and Canada, and significant success cracking the American market. But the U.S. is where anti-gay sentiment gathered steam following George’s 1984 Grammy Awards acceptance speech when Culture Club won for best new artist: “Thank you, America. You’ve got taste, style and you know a good drag queen when you see one.”

It seems inconceivable 40 years later (or would, if not for America’s rabid neo-conservatism) that George referring to himself as a drag queen could spark scandalized pearl-clutching. But he says he was more amused than appalled when the family values mob started staging anti-LGBTQ protests outside concert venues.

Moss provides a droll take on it when he recounts chatting with a Kansas fan who parroted one of the most widely used and offensive homophobic slogans, “God Hates Fags.” When Moss asked the same person, “Are you coming to the show?” they said, “Oh yeah, we love Boy George.” In a Carson appearance, George points up the irony of being considered controversial in a country that had Liberace.

The movie’s most intimate thread concerns the relationship of George and Jon. George says it was “love at first sight,” while Moss, who had never been romantically involved with a man, confesses to being “absolutely smitten,” simultaneously confused and excited. Craig recounts his misgivings about their relationship potentially destabilizing the band. But by the time he voiced his concerns, Moss said it was too late since they had already slept together.

“We were the John and Yoko of the band for a while,” comments George about the resentment of the other two members. But while public displays of affection were the norm between them at the start, that stopped as soon as they had their first hit. Concerns grew that the “secret” of their relationship being exposed could have a ruinous effect on the band. But the doc is inconclusive about the degree to which homophobia drove the backlash or factored in negative reviews of Culture Club’s rushed third album, Waking Up With the House on Fire.

(I was living in London during those years and have to admit I had always assumed George’s sexuality and his relationship with Jon — an important gay dreamboat at the time — were common knowledge.)

There are poignant moments in which Moss looks back on the relationship (“It was really proper love”) and shares the painful process of getting out of it for his self-preservation, while George conveys a more equivocal view, albeit with sadness. One of the major contributing factors to its end appears to have been George’s drug addiction, graduating from weed to heroin in a matter of weeks.

The doc is frank about that dark period and George’s erratic behavior as he began hanging out and getting wasted with fellow genderqueer ‘80s Brit-pop star Marilyn. George’s drug use became tabloid fodder, with Rupert Murdoch’s The Sun predicting he’d be dead before the year was over.

Craig and Hay felt hurt at the time when they were excluded while George and Jon (as well as Marilyn) were invited to participate in the all-star recording of Bob Geldof’s No. 1 Band Aid single, “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” And all three other members express regret about George’s indecision costing the group a spot in the lineup for the historic marathon Live Aid concert at London’s Wembley Stadium.

George sought treatment after multiple friends died of overdoses — including one in the Culture Club singer’s Hampstead mansion — and has been clean now for more than a decade. Is he contrite about the role his drug addiction played in the band’s devolution? Maybe a little, though in his outsize blue velvet bowler and Liz Taylor Cleopatra eye makeup, he mostly comes across as a charming rascal, with not much use for guilt. That made him a great pop star though probably a difficult boyfriend and not the most egalitarian of band members.

Ellwood gives Culture Club and its colorful frontman an affectionate salute that should please fans, even if, unlike the director’s more forthright 2020 Showtime doc, The Go-Gos, she generally chooses diplomacy over a deep dive.

#Iconic #80s #Band #Takes #Bow